So. Dak. So Entrepreneurial

By Robert E. Wright, Nef Family Chair of Political Economy, Augustana

University, Sioux Falls, SD for Sioux Falls Rotary West, Sioux Falls Country Club, 3 June 2016

I often work in my office at Augie late into the

evening to write because it’s quieter and with fewer distractions. So I know

the night janitor in my building better than most. He’s what comedians call a

quote unquote grown ass man, not a kid working his way through college or a retiree

supplementing his income. Most college professors, like my colleague Reynold

Nesiba, would now launch into a diatribe about needing to raise the minimum

wage or the evils and inefficiencies of wealth disparities. They wouldn’t share

their own money with the night janitor, mind you, but they would be happy to

take some of your money to give to him!

But I’m no ordinary professor and South Dakota

is no ordinary state. It turns out that the night janitor is very comfortable

indeed because he owns his own cleaning business. While he toils at Augie, he

has people who work for him, cleaning various businesses around town. When I

asked him where he got such a brilliant idea, he responded that all his family

members had been proprietors at some point in their lives. His specific story

is not in my book, Little Business on the Prairie, but his story fits

the theme perfectly: South Dakota is one of the most entrepreneurial states in

the nation.

The claim that South Dakota is

hyper-entrepreneurial jars most people on the coasts, especially those who

associate entrepreneurship only with high tech startups. In fact, scholars have

identified three types of entrepreneurship: innovative, replicative, and

exploitative. The last mentioned one includes the sorts of activities depicted

in HBO series like The Wire, The Sopranos, and Game of Thrones:

extorting, thieving, killing sorts of activities. Thankfully, we have little of

that here, though I did read someplace that Ian McShane of Deadwood fame

is going to appear on Game of Thrones soon. Of course McShane is British

and not actually from Deadwood.

As measured by patent activity, South Dakota is

not home to much innovative entrepreneurship. South Dakota ranks 49th in total

patents issued but of course its population is about the same as that of Monroe

County, New York, the seat of which is my hometown of Rochester. In per capita

terms, the state still ranks 47th in patent issuance, better than

Arkansas and Mississippi but slightly worse than Alabama. No wonder the state

is called South Dakota.

Seriously, South Dakota lacks several key

drivers of patent activity, large corporations in manufacturing or big pharm --

that is P H, not F, A R M or a large, private research university. Augie’s a

university now, in name, but very small and teaching-oriented and only a

handful of public schools have achieved elite, patent producing status and ours

are not among them.

Of course not all innovative activities can be

patented but measuring them reliably is well-nigh impossible. Measuring

replicative entrepreneurship, by contrast, is relatively easy. Replicative

entrepreneurs extend innovations developed elsewhere to new markets defined by

geography or market segment or niche. It is best measured by proprietorship

income as a percentage of total income or rates of self-employment.

Nationally, since 1990, about 10 percent of

workers have been self-employed. In South Dakota, the figure is almost twice

that. Here is a snapshot from 2012 that shows that self-employment rates in

South Dakota for all major categories are higher than the national average

except for minorities, a point to which I will return shortly.

The vast majority of farmers are self-employed,

replicative entrepreneurs who extend innovations developed elsewhere, at John

Deere and Monsanto say, to the prairies and grasslands. That might seem to give

South Dakota a leg up in the proprietorship stats but they don’t include

agriculture. Here is what they include, which is essentially everything else.

To explain South Dakota’s lead in replicative

entrepreneurship, most people point to its public policies, which are among the

most business-friendly to be found today. The state has one of the highest

levels of quote unquote economic freedom in all of North America and hence the

world. That means that total taxes are relatively low, that entry and exit into

business is relatively easy, that hiring and firing workers is fairly simple,

and so forth.

But the real question is why is South Dakota so economically free? Right next door is a

state that ranks considerably lower on the economic freedom scale, though it

has improved from the days when it was called Taxasota or Mininumfreedomota. Okay,

I made the latter one up. The only way to understand So. Dak.’s high level of

replicative entrepreneurship, I believe, is by studying the state’s history

backwards. I don’t mean ass backwards -- I’ll leave that to my aforementioned

colleague -- I mean we need to ask “What are the root causes of present day

conditions?”

Scholars have shown that high levels of

entrepreneurship lead to … you guessed it, high levels of entrepreneurship. When

people, like Augie’s night janitor, have family and friends who form their own

businesses that gives them the courage and knowledge to do likewise, which gets

yet more people involved in business on their own account. That explanation,

however, is a mere tautology unless we think about why the state’s first inhabitants

were replicative entrepreneurs.

Well, the first Euroamerican residents. American

Indians were obviously the state’s first inhabitants. We know they engaged in

exploitative entrepreneurship well before contact with Europeans. There is a

massive massacre site on the Missouri River called Crow Creek that has been

dated to about 1325 AD. 10,000 years before that, American Indians killed and

slaughtered mammoth in western South Dakota, a clear example of replicative

entrepreneurship. Later, especially in the river valleys, Indians engaged in

agriculture, planting crops, like maize, domesticated elsewhere, again clear

examples of replicative entrepreneurship. If this interests you, I urge you to visit

Blood Run, on the Big Sioux right outside of Sioux Falls, for further details.

If you ever find yourself in Mitchell, check out

the Archeodome on the south side of the lake. Researchers from Augustana

University working there discovered a facility that Indians used to process

bison into pemmican, a mixture of fat and protein that keeps for relatively

long periods. They may have exchanged it for pottery made downriver at Cahokia,

near present day Saint Louis. Not enough of the archeological record survives

to proclaim this innovative entrepreneurship, but it was at least replicative.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government did not just

steal the Indian’s land, which according to the thinking of the day was

justified by non-improvement. What was not justified, by law or religion, was

the destruction of native entrepreneurship. Paternalistic government policies

essentially infantilized Indians, stripping them of the financial and human

capital necessary to start their own businesses as well as the incentives to

grow businesses beyond the nano-stage, as exemplified here by Flossie Bear

Robe’s sewing business.

So it is to the first Euroamerican settlers that

we must turn to for the roots of South Dakota’s entrepreneurial culture. They

were miners in the Black Hills, farmers in the east, and ranchers in between,

along with the wholesalers and retailers who supplied them with life’s

essentials. Here are goods traveling overland before the railroads came in and

here are some fancy goods for sale in Sioux Falls. In short, they were almost

all replicative entrepreneurs, extending mining techniques learned in

California and Nevada, ranching technologies developed in Texas, and farming

systems honed in Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska, and selling goods manufactured

in the Eastern states in ways perfected in that same region.

As I show in Little Business on the Prairie,

which makes a great gift if you are not into nonfiction reading yourself,

replicative entrepreneurship bred more replicative entrepreneurship each

generation ever since. In fact, South Dakota’s history can be told, decade by

decade, as the story of the next “Big Thing,” as a series of hot economic

activities that drove the state’s economy. A sketch appears on my blog,

financehistoryandpolicy.blogspot.com, that’s financehistoryandpolicy all one

word dot blogspot dot com, where I’ll also post a copy of this talk.

Here are some highlights:

Sturgis: an orgy of entrepreneurship as well as of the flesh

The Black Hills lumber industry

The Aeronautics industry: heavier and lighter than air

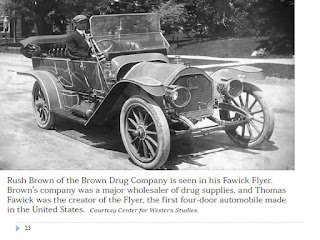

Sioux Falls’ Automobile industry: The famous Fawick Flyer

Tourism as big as the sky

Although Amerindian entrepreneurship was

squelched and hence did not spur the state’s entrepreneurial culture, the

American Indian’s story is an important one because it shows what the state’s

economy would look like if the government were to greatly diminish the economic

freedom of the state’s non-Indians. Incomes East River would not be quite as

low as they are in the state’s Indian Country because the soil is better and

water more plentiful, but they would be much lower than they currently are.

Some of you might be thinking that Indians are

different, even racially or culturally inferior, and that explains the poverty

found on Pine Ridge, Rosebud and so forth. If so, expunge the thought

immediately as it is pure, unadulterated male cattle feces. Indians thrive

economically when allowed to do so and, as the son of an Appalachian, I’ve seen

Euroamericans living in utter despair and squalor in districts run by, and for,

the coal industry.

Thankfully, early South Dakotans endowed us with

a healthy skepticism of government as well as a culture of replicative

entrepreneurship. South Dakota has long possessed one of the most small-d

democratic governments in the world and its constitution is replete with checks

against arbitrary governmental power. One reason that the same political party

was able to dominate the state’s government almost every year for an entire

century was that the electorate, unlike voters in many other states, felt no

need to see-saw back and forth between the parties to maintain some semblance

of balance.

One of those important checks against

governmental overreach, however, appears to be getting out of control.

Generally speaking, ballot initiatives served South Dakota’s citizens well when

the prevailing ethos would not countenance laws that interfered with individual

economic freedom. Due perhaps to the increasingly nationalized K thru 12

curriculum taught in South Dakotan schools and the influx of immigrants from

more liberal, by which I mean statist, places throughout the United States and

abroad, initiatives that would not have been countenanced even a decade ago are

now making it to voters and even winning.

If left unchecked, ballot initiatives may become

too democratic, too much like De Tocqueville’s tyranny of the majority, too

much like two wolves and a sheep voting on the dinner menu. Rather than abandon

ballot initiatives, I think we should limit their scope via the Golden Rule. In

other words, policy X must apply to everybody, not just group Y. For example,

if you believe that the government should be allowed to prevent people from

working unless they earn at least so much per hour, then you should be prepared

to allow the government to set a minimum salary for your particular occupation as

well. Then imagine explaining to your daughter that you lost your job because

your company can only pay you $56,000 per year for a job that the government

says it needs to pay at least $60,000 to fill.

Or, if you believe that some interest rates are

too high and should be capped, then you should be prepared to allow the

government to set all interest rates, which is the same thing as it deciding

who gets credit and who does not. Then imagine explaining to your son that you

cannot buy him an automobile because you cannot find a loan for less than the

6% the government says you are allowed to pay.

In short, right now it is just too easy to vote

to restrict other people’s economic freedom while continuing to enjoy your own.

Too much is at stake here to be decided by a

simple majority on a specific date. As economic freedom deteriorates, so too

will levels of entrepreneurship and that will snap the close connection between

present and future levels of entrepreneurship. Then South Dakota will start to

look like my home state of New York, where people who lose their jobs ask “how

much money can I get from the government and for how long?” instead of “how can

I go into business for myself” as many South Dakotans still do. What they have

in New York and states like it is a vicious cycle of high taxes and

restrictions on hiring and firing necessitated by high levels of unemployment.

That means less economic freedom and hence less entrepreneurship and hence more

need for expensive social programs when the economy turns sour, as it often

does in places that cannot rapidly respond to market changes because of a

dearth of economic freedom. That means more taxes and another spin of the

wheel, or rather another swirl of the toilet water.

If South Dakota turning into New York sounds

far-fetched, keep in mind that the state’s economy has thrice imploded, once

due to drought and migration outflow, once due to drought and restrictions on

economic freedom called the New Deal, and once due to drought, migration

outflow, and restrictions on economic freedom called Nixon’s New Economic Plan

and inflation. Well, to adapt a famous line from Game of Thrones to the West, drought is coming, we just don’t know exactly

when, but it will bring zombie cattle.

The state’s economy is more diverse than it was as recently as the Farm Crisis

of the 1970s and 80s but it is to some extent a Ponzi scheme based on in-migration,

which is a function of jobs and hence ultimately on levels of entrepreneurship

and economic freedom. If migration flows were to stop or, worse, to reverse,

the whole boom could quickly unwind as housing prices drop and construction

jobs dry up.

Trust me on this as I saw it firsthand in my

hometown of Rochester, New York, which lost 34 percent of its population in the

last few decades of the twentieth century. It stabilized soon after I left in

1995 but I’m 99 percent sure my departure was more effect than cause. Okay, 100

percent. The cause was the loss of economic freedom throughout the state that

led Kodak executives to ignore their company’s greatest invention, digital

photography. Given the high tax rate, it was simply too much work to develop a

whole new industry so they milked their cash cow, photograph development, dry until

an east wind just blew it away and its plants had to be shuttered. That’s was a

pun, by the way. Xerox, too, got fed up, first moving its headquarters and then

most of its operations out of the state. Others were not far behind, leaving only

Bausch and Laum to carry on the city’s storied comparative advantage in optics.

Can you tell that I don’t want to be an economic

refugee again? But I also don’t want other people to suffer needlessly. The way

to help the poor is to directly transfer resources to them, not to implement

public policies the unintended ripple effects of which few voters grasp or even

think about.

Thanks for your time and attention. Any

questions about So. Dak.’s long history of entrepreneurship?